By Sandra Marshall

Patrick Imai carves stone bears.

His passion for art matches his enthusiasm for travel. He served 34 years with the Canadian Armed Forces and has been to all provinces of Canada. Having visited over 48 countries on five continents, so why does he specialize in stone bear carving?

While living in Rome, Patrick was moved by its great sculptures and was captured by Bernini’s and Michelangelo’s abilities to make stone come alive. In nearby Carrara he took a workshop in carving a new stone – marble.

Over his lifetime, he has experimented in many artistic media and all types of glasswork, but he has been hooked on carving stone bears – elegant or whimsey, depending on what the stone tells him it should become. It was in his youth that Patrick began to whittle wood as a pastime and developed his skill as a wood carver. A stampede theme of bronco riding tested his wood carving abilities while Calgary was home. Then In Quebec City, Patrick’s interest in stone carving was piqued by delightful Inuit soapstone dancing bears. He was intrigued by their liveliness and challenged himself to learn soapstone carving. By roaming the internet, he learned these techniques and enthusiastically explored that material before working in other soft stones. Patrick carved bears at first because they had drawn him to stonework. He loves the soft curves that make his stone sculpture so appealing. Carving bears is a passion that focuses his attention and takes him to an inner place. After trying to carve other subjects, he found the soft stone did not hold small details and he returned to carving bears with their smooth round forms. We often imbue animals with human characteristics. Building on this association, Patrick evokes human emotions and movement in some of his pieces.In others, he seeks to capture the grace and majesty of the bears. He has highlighted the tragedy of shrinking arctic ice and climate change in several works but does not see his artwork as a political statement. Patrick loves the process and thanks those who acquire his sculptures.

More recently in a cruise port in Alaska, a small bear carved in selenite was spied. Sunlight illuminated the little bear’s movement in the gleaming crystalline stone. Patrick was intrigued, so after the cruise, he searched for selenite pieces large enough to carve. Although it is a challenging stone to carve, its shimmering whiteness makes it a perfect material for carving polar bears.

Patrick’s work in many other mediums helps him to integrate them into his stone sculpture. Glass fish, Muskoka chairs and wooden kayak paddles have served as whimsical props for his humanised bears. He is always on the lookout for other materials to integrate into his sculptures.

Patrick has plenty of stone waiting to inspire him to carve. At times he has an idea and searches for the right stone. When idea and stone converge, carving begins. First, he rough cuts the stone with a hand saw or angle grinder, then hand files and rasps to shape the stone. The process requires a lot of sanding – first dry sanding, then wet sanding and polishing using different grits of abrasive. The final finish is usually a hot wax – Patrick oven heats the stone, and then applies paraffin wax to it. After cooling, he buffs with a soft cloth to give it a satiny finish. At any point in the process, even after waxing, if dissatisfied, Patrick may rework the carving and repeat the process. Until the work is signed, it is not finished.

Patrick’s favorite part of the process is the wet sanding- when the stone reveals its true colours and character. This is the point when the stone comes alive. The rough carving start is his least favorite activity. Although he is enthused to capture his original idea, he also sees other possibilities in the stone as he works.

Aficionados of his work may have tried their hands at these techniques during his many workshops, such as those as the Boys and Girls Club of Ottawa. His carving workshop is also a popular event at the fall Sculpture Show of the National Capital Network of Sculptors at Lansdowne Park. His fans also appreciate his participation in the annual Canadian Stone Carving Festival which raises funds for the Ottawa Innercity Ministries.

His future plans include taking the challenge of tackling hard stone– jade, lapis lazuli and fluorite which involve messy wet grinding. He also looks toward making larger outdoor pieces in harder stone.

For people who may wish to take up sculpture, Patrick recommends workshops. He suggests trying different mediums to find a connection with your personal affinities. Workshops are a way to experience different mediums without the cost or burden of the tools or special equipment. You will also get insight and discover tricks of the trade from an experienced artist. All in all, you will have a better experience, saving time and frustration.

Join a group, like the National Capital Network of Sculptors, where there is a range of artists working in different mediums, using different techniques and are at different points in their artistic endeavours from hobby to professional.

Patrick Imai’s work can be seen on his website www.patrickimai.ca,

His Facebook page https://www.facebook.com/patrick.imai.1

The National Capital Network of Sculptors https://www.facebook.com/SculptureOttawa/

The Gordon Harrison Gallery http://gordonharrisongallery.com/artist/patrick-imai/#btn_readmore

It was a steel wire sculpture made by eight-year old Bastien Martel that set his future direction in art. A camp project of twisting wire into a three dimensional figure was a revelation that he could not forget. His journey in education and art subsequently took many twists and turns – business school, wood working, furniture design and production, painting, drawing and sculpture all had important lessons for him as they lead him from Montreal to Victoriaville, Toronto and then to Honolulu.

It was a steel wire sculpture made by eight-year old Bastien Martel that set his future direction in art. A camp project of twisting wire into a three dimensional figure was a revelation that he could not forget. His journey in education and art subsequently took many twists and turns – business school, wood working, furniture design and production, painting, drawing and sculpture all had important lessons for him as they lead him from Montreal to Victoriaville, Toronto and then to Honolulu. Bastien considered welding classes and programmes but they all seemed too long and involved at the time. It is when he joined Jean-Louis in his studio in Montreal that he had the opportunity to discover metal cutting and welding. It was the perfect opportunity to learn sculptural skills. It also led to discussions: What is art? What makes someone an artist? What does being an artist entail? Bastien was exposed to the many facets of the art world. New techniques were tried –

Bastien considered welding classes and programmes but they all seemed too long and involved at the time. It is when he joined Jean-Louis in his studio in Montreal that he had the opportunity to discover metal cutting and welding. It was the perfect opportunity to learn sculptural skills. It also led to discussions: What is art? What makes someone an artist? What does being an artist entail? Bastien was exposed to the many facets of the art world. New techniques were tried – Martel has worked with wood and stone but found both unforgiving materials. Steel allows him to rapidly create an image and it easily accepts additions or reductions. Steel has the strength to tolerate the abuse of the journey. Bastien’s experience in furniture production and design taught him design concepts, preparation work, planning, measurements and inventory. But mostly it confirmed his love of steel and metals.

Martel has worked with wood and stone but found both unforgiving materials. Steel allows him to rapidly create an image and it easily accepts additions or reductions. Steel has the strength to tolerate the abuse of the journey. Bastien’s experience in furniture production and design taught him design concepts, preparation work, planning, measurements and inventory. But mostly it confirmed his love of steel and metals. In recent years Bastien has explored the breakthroughs of 20th centrury modernist painters using contemporary 3D welded steel. He continues the tradition of objets d’art.

In recent years Bastien has explored the breakthroughs of 20th centrury modernist painters using contemporary 3D welded steel. He continues the tradition of objets d’art. Bastien recently completed series of figurative, portrait and surrealist sculptures, exploring themes of loneliness and isolation. His current exploration is abstraction. He was looking for a quick creative release for feelings of anxiety and confusion created by our imposed Covid confinement. He delved into these emotional states using his clay work technique with welded steel pieces, using the differently shaped metal pieces as his color palette. Between chaos and control, the variously shaped pieces were dropped or thrown onto the clay surface and welded together, in gesturally expressive abstract sculptures.

Bastien recently completed series of figurative, portrait and surrealist sculptures, exploring themes of loneliness and isolation. His current exploration is abstraction. He was looking for a quick creative release for feelings of anxiety and confusion created by our imposed Covid confinement. He delved into these emotional states using his clay work technique with welded steel pieces, using the differently shaped metal pieces as his color palette. Between chaos and control, the variously shaped pieces were dropped or thrown onto the clay surface and welded together, in gesturally expressive abstract sculptures. For others who may wish to take up sculpture, Bastien encourages a studio-based education through college or university, including large components of business management. He recommends this to be followed by apprenticeship with an established artist. There are so many hats an artist must wear and so many skills required for success.

For others who may wish to take up sculpture, Bastien encourages a studio-based education through college or university, including large components of business management. He recommends this to be followed by apprenticeship with an established artist. There are so many hats an artist must wear and so many skills required for success. At a young age, Rocky Bivens’ interest in art was first piqued by museum shows such as a Van Gogh exhibition at the Detroit institute of Art, but he did not engage in the art world at that time. Although he has been a clay artist for over 40 years, Rocky started his adult life in mathematics and philosophy at Oakland University in Michigan. He immigrated to Canada and moved to Toronto working at a warehouse. Then about two years later, he joined a commune in Wabaushene Ontario where he and associates designed and built a geodesic dome, one of the first privately built in Ontario.

At a young age, Rocky Bivens’ interest in art was first piqued by museum shows such as a Van Gogh exhibition at the Detroit institute of Art, but he did not engage in the art world at that time. Although he has been a clay artist for over 40 years, Rocky started his adult life in mathematics and philosophy at Oakland University in Michigan. He immigrated to Canada and moved to Toronto working at a warehouse. Then about two years later, he joined a commune in Wabaushene Ontario where he and associates designed and built a geodesic dome, one of the first privately built in Ontario. second year, he began to teach classes at night. Once he graduated, the school asked him to teach full time. He was drawn to the sculpture-making process in a visceral way, interested in abstract work and insisting on being spontaneous in his methods.

second year, he began to teach classes at night. Once he graduated, the school asked him to teach full time. He was drawn to the sculpture-making process in a visceral way, interested in abstract work and insisting on being spontaneous in his methods. Rocky favours three-dimensional work. Functional and decorative pottery was his initial interest, but he welcomed the challenge and possibilities of clay sculpture, as he became less enamoured in making traditional pottery. He glazed his early sculpture but found that he wanted more control of colour. Now he chooses to glaze some sculptures and for others he employs acrylic paint, playing with colour and texture. Bivens’ sculptures are primarily abstract, anthropomorphic forms. He is strongly moved by form -“from the human abstractions of Henry Moore and essential forms of Constantin Brancusi to the soft, flowing beauty of Auguste Rodin’s La Danaïde and his emotive Burghers of Calais”.

Rocky favours three-dimensional work. Functional and decorative pottery was his initial interest, but he welcomed the challenge and possibilities of clay sculpture, as he became less enamoured in making traditional pottery. He glazed his early sculpture but found that he wanted more control of colour. Now he chooses to glaze some sculptures and for others he employs acrylic paint, playing with colour and texture. Bivens’ sculptures are primarily abstract, anthropomorphic forms. He is strongly moved by form -“from the human abstractions of Henry Moore and essential forms of Constantin Brancusi to the soft, flowing beauty of Auguste Rodin’s La Danaïde and his emotive Burghers of Calais”.

He builds his structures using coils of clay, leaving a hollow centre, important in the drying and kiln firing technicalities. Interestingly, it takes as much time for him to finish the work by smoothing or texturing, as does the construction. Once complete and fully dry, the kiln is fired to about 1,000 degrees Celsius. If he decides to glaze it, he then re-fires the piece to around 1,250 degrees. He may decide instead to use an unfired glaze, such as acrylic paint. Once completed, the painted work is coated with an outdoor rated varnish-like finish.

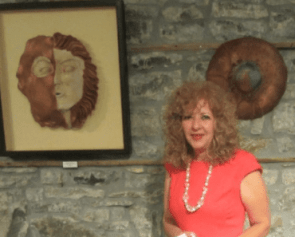

He builds his structures using coils of clay, leaving a hollow centre, important in the drying and kiln firing technicalities. Interestingly, it takes as much time for him to finish the work by smoothing or texturing, as does the construction. Once complete and fully dry, the kiln is fired to about 1,000 degrees Celsius. If he decides to glaze it, he then re-fires the piece to around 1,250 degrees. He may decide instead to use an unfired glaze, such as acrylic paint. Once completed, the painted work is coated with an outdoor rated varnish-like finish. Hengameh’s interest in art began before she left her native land. Although women were not permitted to study pottery in Iran, she persisted in her desire to learn that craft at the ministry of culture in Tehran at the age of 28. Over a period of several years and her courage and determination against denial, she learned wheel throwing and improved her skills by making many vases, opening the way for other women. But she found her life constrained by the political sentiments of the time where authorities forbade the uncovered appearance of the human body in artwork, particularly if the subject was female. People were punished for thinking or dreaming outside of their appointed cultural conditions. Today, her drive to social justice springs from the injustice that she witnessed under the dictatorship. She strives to make us aware that this cruelty will happen in every country if we close our eyes to what is really happening. Hengameh cites a Persian poem that describes her belief:

Hengameh’s interest in art began before she left her native land. Although women were not permitted to study pottery in Iran, she persisted in her desire to learn that craft at the ministry of culture in Tehran at the age of 28. Over a period of several years and her courage and determination against denial, she learned wheel throwing and improved her skills by making many vases, opening the way for other women. But she found her life constrained by the political sentiments of the time where authorities forbade the uncovered appearance of the human body in artwork, particularly if the subject was female. People were punished for thinking or dreaming outside of their appointed cultural conditions. Today, her drive to social justice springs from the injustice that she witnessed under the dictatorship. She strives to make us aware that this cruelty will happen in every country if we close our eyes to what is really happening. Hengameh cites a Persian poem that describes her belief: “If you have no sympathy for human pain

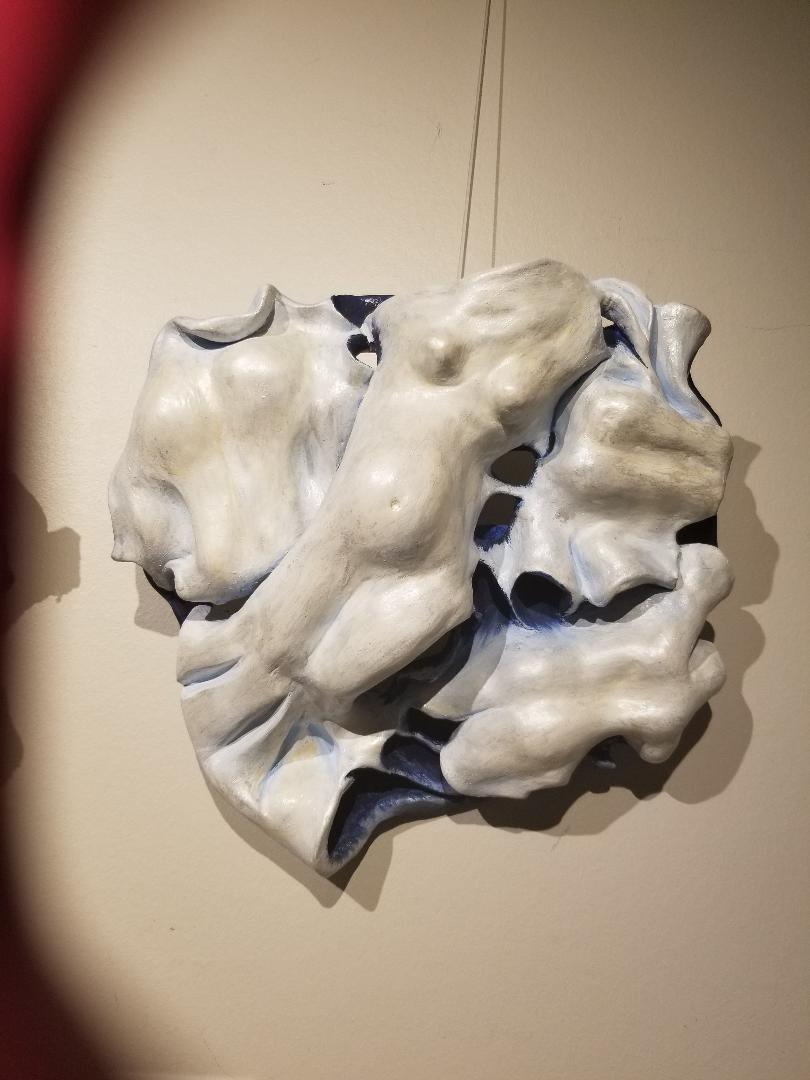

“If you have no sympathy for human pain But clay had left an indelible attraction for Hengameh, and she returned to that medium when she became familiar with the Ottawa art community. She became a member of the Ottawa Guild of Potters to connect to clay artists and began courses at Sunnyside Community Centre, where she could have her work kiln-fired and glazed. Her first Guild sponsored ceramic exhibition was in 1999 when she was accepted to the Guild’s annual pottery sale. This encouraged her to keep improving her skills. When the Sunnyside clay studio was closed, she found the Dempsey Community Centre to continue her passion for clay – hand building rather than wheel thrown work. As Dempsey did not have a kiln, she worked with unfired paper clay, applying an oil patina to solidify the work. Her sculptures were free flowing, following the inspiration that hand-building clay gives her. She designed the pieces for wall hanging, where her delicate pieces would not be damaged. Her process begins with a clay base into which she incorporates elements for hanging her works. Once this preparation is done, she engages with the soft clay, building confidently, moving the clay according to its bidding, moulding the curves with her deepest feelings.

But clay had left an indelible attraction for Hengameh, and she returned to that medium when she became familiar with the Ottawa art community. She became a member of the Ottawa Guild of Potters to connect to clay artists and began courses at Sunnyside Community Centre, where she could have her work kiln-fired and glazed. Her first Guild sponsored ceramic exhibition was in 1999 when she was accepted to the Guild’s annual pottery sale. This encouraged her to keep improving her skills. When the Sunnyside clay studio was closed, she found the Dempsey Community Centre to continue her passion for clay – hand building rather than wheel thrown work. As Dempsey did not have a kiln, she worked with unfired paper clay, applying an oil patina to solidify the work. Her sculptures were free flowing, following the inspiration that hand-building clay gives her. She designed the pieces for wall hanging, where her delicate pieces would not be damaged. Her process begins with a clay base into which she incorporates elements for hanging her works. Once this preparation is done, she engages with the soft clay, building confidently, moving the clay according to its bidding, moulding the curves with her deepest feelings. In 2011, Hengameh Kamal Rad joined the National Capital Network of Sculptors. The fact that two of her juried works of fired paper clay were part of the 2013 sculpture exhibition at the Museum of Nature in Ottawa, gave her positive feedback. Her sculptural work is energized by the outdoors – the glorious flow of water and snow. The mysteries of design in nature and space, of life and reproduction are all part of her creations.

In 2011, Hengameh Kamal Rad joined the National Capital Network of Sculptors. The fact that two of her juried works of fired paper clay were part of the 2013 sculpture exhibition at the Museum of Nature in Ottawa, gave her positive feedback. Her sculptural work is energized by the outdoors – the glorious flow of water and snow. The mysteries of design in nature and space, of life and reproduction are all part of her creations. Edna’s life had a somewhat royal beginning, as her parents were employed by Britain’s Royal Household and they lived in the Royal Mews in London, England. As a girl she had wonderful freedom to roam and explore the stables, and nearby St. James Park and Hyde Park. Her life was filled with visions of huge horses, carriages, blacksmithing, all manner of birds, fish, flowers and trees that have become inspiration for her artwork. Edna’s first art impulses were sparked by the colourful and free illustrations of impressionists Van Gogh and Gaugin in her school classrooms. After high school she turned to courses in technical illustration. Adept at this work, she was later able to skillfully translate the plans and elevations of mechanical equipment into 3-dimensional drawings, a skill still useful in building her 3D sculptures.

Edna’s life had a somewhat royal beginning, as her parents were employed by Britain’s Royal Household and they lived in the Royal Mews in London, England. As a girl she had wonderful freedom to roam and explore the stables, and nearby St. James Park and Hyde Park. Her life was filled with visions of huge horses, carriages, blacksmithing, all manner of birds, fish, flowers and trees that have become inspiration for her artwork. Edna’s first art impulses were sparked by the colourful and free illustrations of impressionists Van Gogh and Gaugin in her school classrooms. After high school she turned to courses in technical illustration. Adept at this work, she was later able to skillfully translate the plans and elevations of mechanical equipment into 3-dimensional drawings, a skill still useful in building her 3D sculptures. In 1962, newly married, she and her husband Clement moved to Quebec City where he became a professor at Université Laval. As their family grew from none to four children, Edna took evening art classes where she was introduced to new concepts each month, such as leather work and painting nature. She found it a relief to be engaged in these creative activities while adjusting to her new home and new language.

In 1962, newly married, she and her husband Clement moved to Quebec City where he became a professor at Université Laval. As their family grew from none to four children, Edna took evening art classes where she was introduced to new concepts each month, such as leather work and painting nature. She found it a relief to be engaged in these creative activities while adjusting to her new home and new language. With some colleagues after university, they found rental space in unused buildings where they worked on projects together and even rented advertising space in buses to show their work. It was very reassuring to Edna to be with other artists and to see their unique patterns of work. When the studio spaces became unavailable, Edna began to work from home, but she needed, in Virginia Wolf’s words, “a room of one’s own”. Her personal studio became a creative world of her own. This space gave Edna the freedom to develop her artistic individuality. She says that it’s a very messy place but a personal oasis for her to expand and grow.

With some colleagues after university, they found rental space in unused buildings where they worked on projects together and even rented advertising space in buses to show their work. It was very reassuring to Edna to be with other artists and to see their unique patterns of work. When the studio spaces became unavailable, Edna began to work from home, but she needed, in Virginia Wolf’s words, “a room of one’s own”. Her personal studio became a creative world of her own. This space gave Edna the freedom to develop her artistic individuality. She says that it’s a very messy place but a personal oasis for her to expand and grow. Papier mâché captured her attention when she spied the work of Victor Tolgesy hanging from the ceiling of the Byward Market Building. She contacted him for information about the process and she found him very accommodating and kind. Tolgesy’s work appealed to Edna’s sense of play and joy. She was also influenced by René Magritte as she recognized that he changed visual reality into his own creative reality where anything was possible.

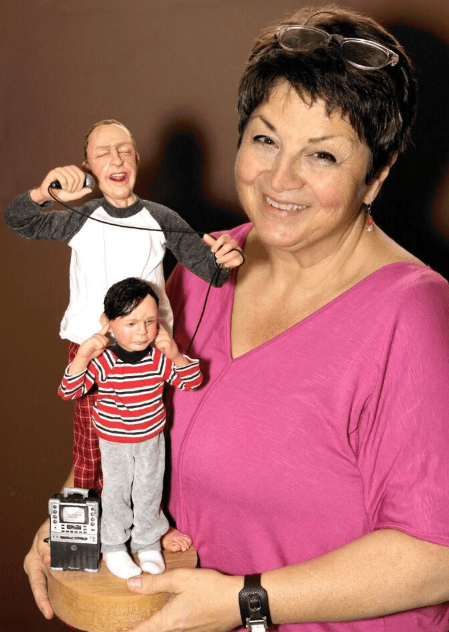

Papier mâché captured her attention when she spied the work of Victor Tolgesy hanging from the ceiling of the Byward Market Building. She contacted him for information about the process and she found him very accommodating and kind. Tolgesy’s work appealed to Edna’s sense of play and joy. She was also influenced by René Magritte as she recognized that he changed visual reality into his own creative reality where anything was possible. with an image in her mind which is not well defined. Using papier mâché allows her to make changes and offers her hands the impetus toward her vision of the finished product. This process begins by drawing on a foam board. She then builds a skeleton using strong wire which is glued to the foam core. At this stage the framework can be twisted and bent to achieve the desired shape. Multiple layers of newspaper are applied with glue to build the shape. The glue, Natura, is allowed to dry between each additional layer. For the final layer, paper towels are applied before finishing the work with acrylic paint.

with an image in her mind which is not well defined. Using papier mâché allows her to make changes and offers her hands the impetus toward her vision of the finished product. This process begins by drawing on a foam board. She then builds a skeleton using strong wire which is glued to the foam core. At this stage the framework can be twisted and bent to achieve the desired shape. Multiple layers of newspaper are applied with glue to build the shape. The glue, Natura, is allowed to dry between each additional layer. For the final layer, paper towels are applied before finishing the work with acrylic paint.

“With the galleries being closed I’m not particularly motivated to create new works. I’m trying to work on some online workshops and tutorials but needed a little boost. In my trade show days as a graphic designer, 25+ years ago, I used to do stage design and some contract work with an interior decorator. I would do colour coordinated oversized paintings for large walls – very loose abstracts or florals. We recently moved so I decided to do a colour schemed texturized acrylic painting for my new bedroom to coordinate with my bedspread. It works . . . and the creative juices are starting to stir again.”

“With the galleries being closed I’m not particularly motivated to create new works. I’m trying to work on some online workshops and tutorials but needed a little boost. In my trade show days as a graphic designer, 25+ years ago, I used to do stage design and some contract work with an interior decorator. I would do colour coordinated oversized paintings for large walls – very loose abstracts or florals. We recently moved so I decided to do a colour schemed texturized acrylic painting for my new bedroom to coordinate with my bedspread. It works . . . and the creative juices are starting to stir again.”

studios I model for as a Life-Drawing model.

studios I model for as a Life-Drawing model.